Inside the Magnificent Fall Armyworm Parasitoids Lab in Alupe

Posted on

Any time a farmer hears of fall armyworms, he or she falls back on the sickening thought of a creature capable of turning his or her life upside down.

Farmers in Kenya have desperately tried a variety of methods to combat these damaging pests in their maize crops, with little or no success. They put into practice measures, both traditional and modern, such as the use of neem-based solutions, ash and pesticides. Pesticides have proved very ineffective due to their toxicity to plant, animal, and human life and the fact that pests easily develop a resistance to them.

The most thoughtful way to control the pests recommended by experts is to use biological means, which, apart from being very effective, are also friendly to the environment.

An adult fall armyworm on a maize plant leaf [Photo-Courtesy]

An adult fall armyworm on a maize plant leaf [Photo-Courtesy]

It is for this reason that PlantVillage, through the Dream Team Agro Consultancy Limited in collaboration with USAID's Current and Emerging Threats to Crops, set up a parasitoids rearing lab at Alupe University in Busia County, Kenya.

Brenda Cheptoo is one of the leads in charge of the daily activities in the lab that never closes its doors.

"Our parasitoids lab became functional in October 2021. We are a team of nine with the aim of producing 30 million parasitoid eggs by the end of this year for farms in 10 counties in Kenya," she says.

The parasitoids lab team at work [Photo-PlantVillage]

Rearing parasitoids in the lab starts by establishing fall armyworm colony by collecting larvae from the field and then innoculating them with natural or artificial diet in lunch boxes or vials until pupation and then transferring them to emergence and oviposition cages, a process that follows successive and carefully executed steps that involve feeding and taking care of the organisms through larval, pupal, and adult stages where they lay eggs (hosts) that will eventually be glued on cards ready for parasitism To avoid contamination, fall army worm larvae collected from the field have to be reared for up to two generations in the lab before the eggs are exposed to parasitism.

"The first activity in the lab is to harvest fall armyworm eggs from the oviposition cages, which we do early in the morning. We then prepare special cards before exposing them to the fall armyworms. One card accommodates 10,000 to 12,000 eggs," he says.

Oviposition cages [Photo-PlantVillage]

Frank says that two species of parasitoids are reared in a special room. The room has a refrigerator for storing larval diet, extra host eggs, and storing or chilling adult and pupal parasitoids before transfer to the field for release, a microscope for identification of parasitoids and their sex, and an incubator for maintaining an optimal temperature for parasitoid larval and pupal development.

Feeding the larvae

Above all this comes the tedious work of preparing a natural diet for the fall armyworm larvae, which Frank says consumes a lot of time and requires the input of the whole team. The diet is made up of fresh maize leaves.

"This is a daily activity. To prevent canibalism, we sought the larvae in instas. We change the diet in lunchboxes to prevent infections from fall armyworms. The diet is made up of tender leaves, mostly from maize crops," he adds.

Natural diet for fall armyworm larvae consisting of tender maize leaves [Photo-PlantVillage]

Apart from the natural diet, there is also an artificial diet given to the larvae. Preparing it is equally time-consuming and procedural as well as requiring a level of expertise, which Brenda Cheptoo has mastered.

All she needs for the larvae delicacy is found in the kitchen: a supply of beans, Brewer’s yeast, wheat germ, an electric cooker, a weighing balance, utensils, and ingredients. The recipe is at her fingertips.

Brenda Cheptoo ready to prepare an artificial diet for the fall armyworm larvae [Photo-PlantVillage]

"The diet is fortified with vitamins and minerals to keep the parasitoids in good health. Preparing the food requires careful steps not to mess up and spoil the whole thing," she says.

One would easily confuse the meal for some nutrious porridge. Of course it is nutrious, Brenda says, but only meant for nurturing the parasitoids ahead of their important task of fighting fall armyworm in the field.

The food is cooked with the help of a section of the crew at the lab into a porridge-like mixture, and when ready, it is dispensed into vials fashionably arranged in the diet infestation room.

The emergence and oviposition cages

Valentina is the third talent at the lab. She explains that the vials are then covered with cotton wool to absorb excess moisture from the diet and prevent fall armyworm larvae from escaping.

It is at this juncture that the young ones of the fall armyworms are innoculated. It takes 14 days for the larvae to pupate and be ready for harvesting.

Innoculated fall armyworm larvae in test tubes covered with cotton in the diet infestation room [Photo-PlantVilage]

"After that, we harvest the pupae and place them in emergence cages," she says.

Once the pupae are harvested, they are transferred to emergence and oviposition cages where they are provided with moisture and fed with 50% honey after emergence.

"They prefer to lay eggs during the night, that's why we use a dark room to provide those conditions," he says.

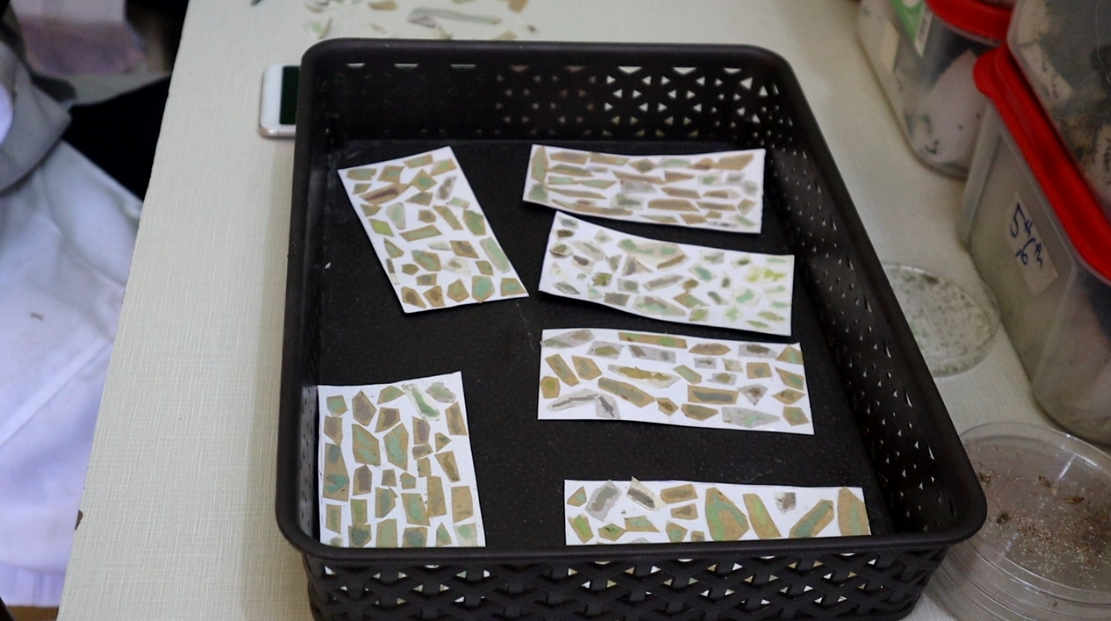

A petri dish of cards containing fall armyworm eggs.One card can accomodate 10,000 to 12,000 parasitized eggs [Photo-PlantVillage]

The eggs are then glued onto cards specially prepared to hold between 10,000 and 12,000 eggs. They are, at this point, ready to be transported and released into fields of maize.

The lab has already given out more than 25 million parasitoid eggs to fight fall armyworm in 10 counties in Kenya, a project that is proving effective.

Brenda Cheptoo says this is only but the beginning as they target to release 30 million this season.

- Written and photographed ]by Sam Oduor